An Hour By Hour Timeline of The Titanic Sinking

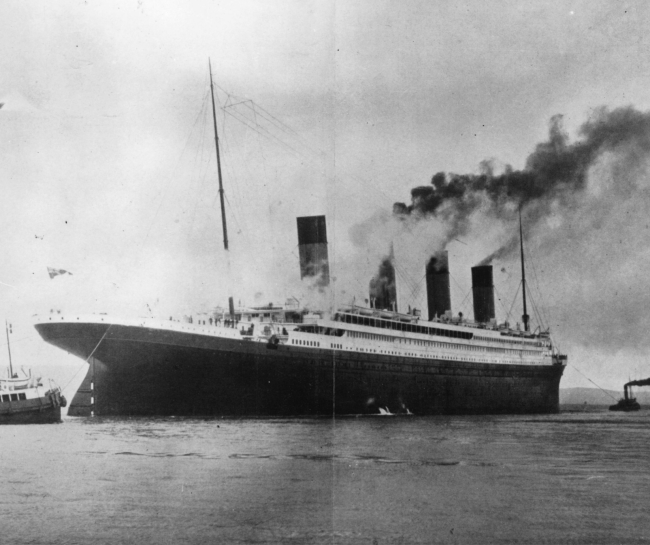

It is April 10th 1912, and the breathtaking Titanic leaves Southampton, England, carrying with it the hopes and aspirations of about 2,200 souls, including approximately 1,300 passengers.

Little does anyone onboard realize that in just 4 days, the unthinkable will happen.

Following the Detailed Journey of the Titanic Sinking Hour by Hour

So, let’s retrace the fateful days and hours leading up to the tragedy that forever etched this ship’s name in history.

1. The first day of the Titanic voyage

The day begins with a buzz of anticipation. Wealthy people, like the renowned business magnate Benjamin Guggenheim, Macy’s department store co-owner Isidor Straus and his wife, Ida or journalist William Thomas Stead, step aboard. Their presence adds an unmistakable air of prestige. At the helm is the experienced Captain Edward J. Smith, a man whose reputation as the “Millionaire’s Captain” resonates with the elite onboard. Additionally, Thomas Andrews, the designer of the Titanic is also travelling on the ship.

However, the excitement of departure gives way to a moment of anxiety. As the Titanic pulls away from the dock, her powerful engines churn the water, causing the nearby docked ship, the New York, to drift dangerously close. For an hour, it’s a battle of wits and maritime skill, but the potential disaster is skillfully averted, and the Titanic continues its journey.

Later in the day, as the sun dips below the horizon, the Titanic reaches Cherbourg, France. The dock is too small for the gigantic liner, so the passengers, among them the distinguished John Jacob Astor and Molly Brown, are ferried to and from the ship. Despite the minor inconvenience, the air remains charged with anticipation.

As night falls, the Titanic, fully laden and abuzz with activity, cuts through the dark waters of the Atlantic. The ship is a moving city, a beacon of human achievement. But underneath the celebration, an unforeseen tragic destiny is brewing.

If you can’t get enough of these Titanic stories, we recommend you also read 15 Bone-Chilling Titanic Facts No One Knew!

2. The next 3 days of the Titanic voyage

On the morning of April 11, the Titanic docks in the harbor of Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland, its last European stop. The ship takes on board last-minute cargo, mail, and passengers.

As the dockside activity begins to wind down, the Titanic sets sail once more at approximately 1:30 pm, now pointed towards New York City.

The following days on board the Titanic present a world teeming with life. The passengers, hailing from the richest aristocrats to hopeful emigrants, begin to explore the ship and enjoy the trip.

Amidst this, the ship’s crew is a hive of activity. John Starr March of New Jersey, aged 48, is a mail clerk, working in the fully operational mail-sorting facility aboard the Titanic.

In the Marconi room, located on the Boat Deck, Jack Philips and Harold Bride send and receive messages via the wireless telegraph system. It is one of the most powerful radio telegraph systems of any ship in the world and very popular among the Titanic’s rich passengers. Everyone wants to send countless personal and business messages or news, making the wireless a busy service. There’s very little time to listen to any iceberg warnings coming in.

So, as the Titanic carves its path through the cold Atlantic, life aboard continues in blissful ignorance. Little do they realize that their world is ticking down to a moment frozen in time, soon to be remembered as one of the most tragic maritime events in history.

3. The morning and afternoon of 14th April 1912

It’s a brisk Sunday morning on April 14, 1912. The icy air prompts Captain Edward J. Smith to call off the lifeboat drill scheduled for the day.

With a backlog of passenger telegrams from the previous night to catch up on, wireless operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride find themselves busy. To make matters worse, the wireless system had suffered a malfunction and was out of action for several hours.

As telegrams flood in, iceberg warnings from nearby ships fall in the background. While they catch the attention of Captain Smith and the ship’s owner, Bruce Ismay, the fair weather gives them little cause for alarm. Despite this, Smith adjusts the ship’s course slightly south to take it into warmer and safer waters.

The temperature drops as evening creeps in. Passengers retreat indoors, leaving the decks empty in the biting cold. Second Officer James Lightoller is at the helm.

Wireless operator Harold Bride, mindful of the stress on the radio system, decides to give it a rest around 7:15 pm. Meanwhile, Captain Smith enjoys a fine dinner with distinguished guests.

Returning to the bridge at around 8:55 pm, Smith discusses the dropping temperatures with Lightoller, who warns that the conditions will likely reach freezing during the night. Smith retires for the evening, reminding Lightoller to slow the ship in case of haziness and to keep a keen eye for icebergs.

The wireless room remains a hive of activity, as the operators communicate a mass of telegrams to the mainland. An ice warning from the steamer Mesaba goes unheeded, drowned in the flood of messages.

4. It’s 10 pm!

As 10:00 pm rolls around, passengers begin to retire to their rooms. In the mail room, John Starr March and his colleagues gather around to celebrate the 44th birthday of another American mail clerk aboard, North Carolina-born Oscar Scott Woody.

Handing over the helm to First Officer Murdoch, Lightoller briefs him on the Captain’s orders before turning in for the night. Lookouts Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee begin their watch in the Titanic‘s crow’s nest.

Phillips is still juggling a whirlwind of messages when an urgent transmission from the Californian slices through the cacophony: “Say, Old man, we are stopped and surrounded by ice.” But the harried Phillips, agitated and overworked, snaps back, “Shut up! Shut Up! I am busy.”

In the deadly silence of the moonless night, with no waves to betray their presence, icebergs loom in the Titanic’s path. As the clock ticks toward an uncertain future, the ship steams on, oblivious to the warnings that had been issued.

5. It’s 11:00 pm!

At 11:39, Frederick Fleet spots a menacing silhouette in the ship’s path. It’s an iceberg. With a jolt of alarm, he rings the bell three times and phones the bridge. On the bridge, First Officer William Murdoch responds with a swift “hard-a-starboard” order, commanding the ship to veer to the left. The engines are thrown into reverse.

But it’s too late.

At 11:40 PM, a shuddering scrape echoes through the hull as the starboard side of the Titanic grazes along the iceberg. As ice chips cascade onto the deck, Murdoch swiftly orders a ‘Hard to Port!’ turn to protect the propellers from the looming iceberg. Hichens, at the wheel, steers the ship starboard, narrowly clearing the iceberg’s path. Despite the quick maneuver, the ship scraped the iceberg for a tense ten seconds.

Alarmed by potential flooding, Murdoch quickly rings a warning bell and seals the watertight compartments. The ship’s engineers and firemen scramble through the rising icy waters and up ladders to escape the sealed doors.

Many onboard, especially those towards the starboard and bow felt a mild jolt.

Doctor Washington Dodge, travelling first class with his wife and child, wakes up at 11:40 PM. He heads out onto the deck twice, asking if everything is okay. Each time, he’s told not to worry, there’s no danger. Feeling reassured, and noticing the general calm among other passengers and officers, he tells his family to stay put, stay in bed, and wait for any new developments.

Awoken by the collision, Captain Smith arrives at the bridge and orders a thorough assessment of the damage.

Reports soon arrive that water is rapidly filling the mail hold and other sections. Smith prepares wireless operators Phillips and Bride for a potential distress call and proceeds with Andrews to evaluate the damage.

At 11:45 PM, as the inspections are carried out, the ship grinds to a halt. Two minutes later, Captain Smith orders the engines to ‘Half Ahead’. By 11:49 PM, over a million gallons of seawater have already seeped into the ship.

Given the extent of the damage and the rapid water rise of 14 feet above the keel within ten minutes, Andrews estimates Titanic’s survival at no more than 90 minutes. Confronted with this grim prognosis, Smith directs his officers to ready the lifeboats and ensure passengers are equipped with lifebelts. Chief Officer Wilde is tasked with assembling the deck crew and preparing the boats, while First Officer Murdoch is instructed to alert the passengers, and Sixth Officer Moody is assigned to locate the lifeboat station list. Smith then proceeds to the Marconi Room to instruct the wireless operators to transmit the international distress signal, providing the coordinates for potential rescuers.

At 11:56 PM, all engines are ordered to stop for the final time. At 11:59 PM, the grand Titanic, once the symbol of mankind’s ambition, coasts to her final, haunting stop.

6. It’s 12:00 am, 15th April, and the countdown begins!

At midnight, the order to ready the lifeboats, rouse the passengers and gather the crew is given. The ship’s 20 lifeboats can only hold 1,178 people, far less than the 2,200 on board. Women and children are prioritized to board first, with crewmen assigned to steer the boats.

They decide to release pressure and vent the extra steam from the boilers to avoid explosions. Firemen work quickly to extinguish the furnace fires to cool the steam, which results in a lot of noise on the ship’s deck.

By 12:06 AM, the First Class Lounge is set as the evacuation assembly point. Nine minutes later, wireless telegraph operators John Phillips and Harold Bride receive Captain Smith’s order to prepare a distress signal. Both the official SOS and the older CQD code are transmitted over the next few hours, but responding ships, including the Titanic’s sister ship, the Olympic, are too far away to provide immediate help.

Dr. Washington Dodge, having confirmed the seriousness of the situation, swiftly guides his family to the starboard boat deck. Simultaneously, several onboard spot the lights of another ship, later identified as the SS Californian, about 10 miles away.

Officer Boxhall proposes a distress signal to the nearby ship, only to learn that Captain Smith has already sent one. However, the ship’s reported position was wrong and Smith orders Boxhall to calculate their exact location.

Unfortunately, the SS Californian was unreachable since its wireless communication had been shut down for the night.

At 12:16 am, amidst the chaos and uncertainty, the soothing strains of music begin to flow from the Lounge. The orchestra has started playing, in an effort to calm the passengers, as the Titanic starts a noticeable lean to its right side.

Meanwhile, a plea for help rockets through the airwaves, from the Titanic to the Carpathia, a ship sailing 58 nautical miles away. “We’ve hit an iceberg. We need immediate help,” the signal reads. Upon receiving this distress call, the Carpathia alters its course without hesitation, embarking on a race against time to reach the stricken vessel. However, it’s estimated to take more than three hours to arrive.

Back on the Titanic, Fourth Officer Joseph G. Boxhall is busy recalculating their coordinates. He promptly updates the ship’s location in the distress signals.

At 12:32, the majority of lifeboats are readied for departure. Eight minutes later, Lifeboat 7, despite its capacity for 65 passengers, departs the ship carrying only 28 individuals, 26 of whom are first-class passengers.

Despite the tragic insufficiency of lifeboats, the Titanic still met the requirements of the Board of Trade, the maritime safety regulator of that time. In those days, the number of lifeboats was determined by the ship’s size, not its passenger capacity. These regulations, last updated in 1894, were based on ships weighing around 10,000 tons – a far cry from the Titanic’s 46,328 tons.

Moreover, accessibility to lifeboats varied across classes. First and second-class passengers could easily reach the boat deck via staircases, but for third-class passengers, the journey was a lot more difficult. The plan was to lower lifeboats from the boat deck and then pick up additional passengers from the lower decks. However, due to the lack of boat drills and crew training, the lifeboats were launched without making the intended stops.

Consequently, third-class passengers were at a severe disadvantage. While most first and second-class women and children survived, most third-class women and children perished. Of the 29 children travelling in first and second-class, only one, a two-year-old Canadian girl named Lorraine Allison, lost her life. In contrast, 53 of the 76 children travelling in third-class did not survive.

At about 12:43, Lifeboat 4 is lowered to A-Deck for boarding, but due to the crew’s inability to open the A-Deck windows, it sits idle for a while.

One minute later, Lifeboat 5 becomes the second to leave the Titanic, carrying 36 passengers. As it descends, two men leap into the boat, injuring a woman onboard. This scene sends a shockwave of panic through J. Bruce Ismay, who desperately yells to lower the lifeboats. He is scolded and pulled away by Officer Lowe. There’s a hiccup with the lifeboat’s lowering mechanism that causes the front of the boat to dip, but by 12:45, Lifeboat 5 launches properly.

Around this time, the D-deck gangway doors open to aid in the loading of lifeboats, but they are never used.

Lifeboat 6 launches with passengers Molly Brown and lookout Fleet, under the command of Quartermaster Robert Hichens. His refusal to look for survivors later earns him the wrath of his passengers, especially Brown, who threatens to toss him overboard.

At 12:45, the rear watertight doors open to allow the pump crew access.

Two minutes later, a group of stokers rush up the Grand Staircase, alarming the passengers.

At 12:50, Lifeboat 9 is lowered to A deck by Chief Officer Wilde, with the other starboard lifeboats preparing to follow.

Three minutes later, the Strauss couple famously refuse to separate at Lifeboat 8. Mrs Strauss insists that her maid take her place in the lifeboat.

By 12:55, Lifeboat 3 is launched with 32 passengers on board.

And, at 12:58, the musicians move to the deck, continuing to play their music amidst the chaos.

7. From 01:00 am to 02.00 am, the chaos intensifies

At around 1:00 – The 27 passengers of Lifeboat 8 push away from the Titanic.

At approximately 1:05 – A small lifeboat, Lifeboat 1, designed for emergencies, floats away with only 12 people on board, though it could hold 40. The famous first-class passengers Sir Cosmo Edmund Duff-Gordon and his wife, Lucy, are among them, along with seven crewmen. Later, rumors spread that Duff-Gordon might have bribed the crew with £5 each to stop them from picking up more survivors.

At about 1:07 – Crew members work hard to assemble and start suction pumps in the flooded sections of the ship.

At roughly 1:15 – The seawater reaches up to the nameplate on the Titanic’s hull.

At around 1:18 – The Titanic begins to tilt to the left side.

At about 1:20 – The vast majority of the engineering and stoker teams are told to leave their posts, and Lifeboat 16 is launched with 53 people on board.

By approximately 1:22 – The crew is forced to abandon Boiler Room 4.

Close to 1:23 – The Titanic tilts even more to the left.

At around 1:25 – Lifeboat 14 leaves the Titanic with 40 people on board. Officer Lowe uses his revolver to scare off a crowd of men trying to jump into Lifeboat 14 from the A-Deck Promenade. By this time, most passengers realized there are not enough lifeboats for everyone, creating a chaotic scene on the deck.

At approximately 1:29 – Revolvers are handed to all the officers of the Titanic for their protection.

At around 1:30 – Lifeboat 12, carrying 42 people, moves away from the doomed ship. Lifeboat 13 is also launched, soon to be followed by Lifeboat 15, which carries many third-class passengers. As Lifeboat 15 is being lowered, it comes dangerously close to landing on Lifeboat 13, which has drifted beneath it. However, the quick-thinking crew in Lifeboat 13 manages to cut the launch ropes and row to safety.

Around 1:40 – Collapsible C, another lifeboat, is prepared for lowering. Among those boarding it is J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman of White Star Line, the company that built the Titanic. He will later insist that he only boarded the lifeboat because there were no women or children nearby. Others will contradict this claim, and Ismay will face public scorn for not going down with the ship.

At approximately 1:45 – Lifeboat 2, an emergency cutter, is launched with Fourth Officer Boxhall in command. Around 20 people manage to board it. In the same minutes, Lifeboat 11 is lowered into the sea with about 50 passengers.

At about the same time, Lifeboat 4 is prepared for launch. A young, pregnant woman named Madeleine Astor is helped into the lifeboat by her husband, John Jacob Astor. When Mr. Astor requests to join his wife, Second Officer Lightoller, who has been strictly following the ‘women and children first’ rule, denies his request. Astor doesn’t argue and steps back. Sadly, he won’t survive the night, and his body will be recovered later.

8. 2:00 am – 3:00 am – the last hour!

At about 2:00 AM, the sinking bow reveals the ship’s stern propellers above the water. Crewmen manage to lower collapsible lifeboat D from the officers’ quarters, carrying over 20 passengers.

As the bow submerges, collapsible A is washed from the deck. Around 20 people scramble into the partly flooded boat, but only 12 survive. In the chaos, collapsible B falls and is swept away, offering refuge to 30 men, including wireless operator Bride and Second Officer Lightoller.

At this point, Captain Smith releases his crew, saying that “it’s every man for himself”; his body will never be found.

At about 2:18 AM, darkness engulfs the Titanic as its lights fail. The bow sinks further, causing the stern to lift higher, resulting in the ship breaking in two. The stern momentarily steadies then rises again, stands briefly vertical, and begins its final descent.

By 2:20 AM, the Titanic vanishes beneath the sea. The stern implodes due to water pressure, landing around 2,000 feet from the bow. Hundreds are left in freezing water, and despite room in lifeboats, the crew delay rescue. Only a few are saved.

9. The Aftermath

At about 3:30 AM, the Carpathia emerges, lighting up the darkness with fired rockets. The rescue operation begins, with lifeboat 2 being the first to reach the Carpathia at around 4:10 AM. The process of picking up all survivors extends for several hours. Amid this, Ismay composes a sorrowful message to the White Star Line’s offices, announcing the tragic loss of the Titanic and the significant loss of life.

Finally, at about 8:50 AM, the Carpathia, bearing the 705 survivors, embarks on its journey to New York City. When it arrives on April 18, the city greets the vessel with massive crowds.

In conclusion, the sinking of the Titanic in the early hours of April 15, 1912, stands as one of the most tragic maritime disasters in history. The loss of life was catastrophic, and the event left a profound mark on society, leading to significant improvements in maritime safety regulations.

In the end, we’d like to point out that this account is composed of the many narratives shared by survivors. The timing of the events may not be precise, as people’s recollections can vary based on their perspectives and experiences during that night of chaos and despair. Nevertheless, every retelling keeps alive the memory of those lost and the lessons learnt from the tragic sinking of the Titanic.